With the rise of bourgeois nations in the 19th century, national allegories became increasingly popular in all European states. A national allegory is a figure that embodies a nation and the characteristics typically assigned to it. In most cases, female figures were used for this kind of personification – but there are also national allegories in the form of animals and abstract shapes.

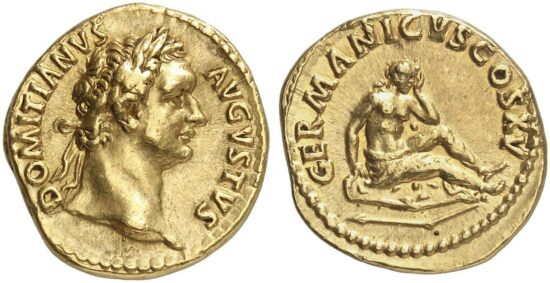

The concept of using female figures as personifications of places and territories is actually much older. In addition to the gods of the pantheon, who were most important, there were countless regional protective deities in late antiquity. We know about these deities from tales and works of the visual arts, but also from (early) Greek and Roman coinage: there are personifications of Africa, Britannia, Gallia, Germania, Juaea and Europe, for example. Initially, such specimens were minted in Rome to celebrate successful military campaigns, emphasising the difference between certain regions. Later, Emperor Hadrian (AD 76/117 to 138) deliberately depicted the patron goddesses of the imperial provinces on his coins to create a sense of unity (German Wikipedia: List of National Allegories).

A collection of Marianne depictions in the office of the former President of the French Constitutional Council, Jean-Louis Debré. Photo: ShrimpMan, CC-BY-SA 3.0

Marianne

To begin with, Marianne was just an old French first name, composed of Marie and Anne. According to Christian tradition, the name refers to Mary, the mother of God, and Anne, the mother of Mary. During and as a result of the French Revolution, Marianne became a symbol of freedom and the Republic. Today, Marianne represents the French nation in many depictions: her bust can be found in almost every French town hall, and her statue in many squares of the country. In addition, she is depicted on stamps, coins and telephone tokens, which were used in the past.

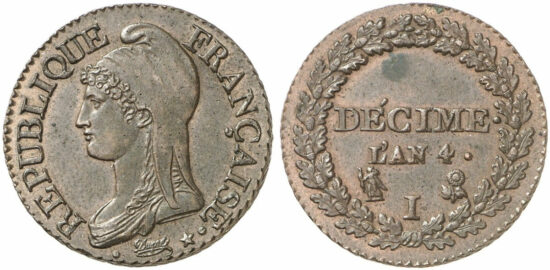

Personifications on Coins of the First and Second Republics

“The first written source mentioning Marianne as the name for the French Republic is from October 1792, from Puylaurens in the Departement of Tarn. At that time, people sang the song ‘La garisu de Marianno’ (Engl: Marianne’s recovery) by the poet Guillaume Lavabre” (German Wikipedia: Marianne). However, the depiction of a head with a Phrygian cap on coins of the First and Second Republics (1792 to 1799/1804 and 1848 to1852), which were designed according to the new decimal system, did not yet refer to Marianne as a national personification – these depictions were personifications of Liberty (Type Augustin Dupré) that are similar to the images on the coins of numerous other European and American states that were fighting for independence at the time.

Moreover, there are depictions of the personified Republic: The head of the Republic on 10- and 20-franc gold coins minted from 1849 until 1851 (Type Merley) bears ears and oak leaves representing fertility, strength and resistance. To the left there is a bundle of rods symbolising unity and power – without an axe, indicating assertiveness without death penalty – and to the right an olive branch as a symbol for prosperity and peace throughout the Republic and among the people. All this tells us that the coin designs of the time clearly distinguished between symbols of the Republic and symbols of liberty.

France, 3rd Republic. 50 centimes, 1897. First year with the motif of the female sower. From Künker auction 131 (2007), lot 4106.

Coinage of the 3rd Republic

The first issues of the Third Republic (1871 to 1940) used the image of the fertility goddess Ceres, that of the Republic and the depiction of the Hercules group. In 1897, a new coin motif was introduced, which is used to this day: the female sower. The legend of the coin reads: je sème à tout vent – I sow to every wind. Following the model of Charlotte Ragot (Type Louis-Oscar Roty), a woman wearing a long robe and a Phrygian cap with waving long hair strides across the countryside in front of the setting sun (on the right of the image). She carries a bag of seeds over her left shoulder and spreads it with her right hand. The sower can be interpreted as a personification of France, rather referring to the care of the state than to the combative side of liberty (Phrygian cap) and the strength or resistance of the Republic and the people (oak leaves).

France, 3rd Republic. 10 centimes 1906, with Marianne (Type Daniel Dupuis) and Minerva. From Künker auction e-Live 71 (2022), lot 521.

Distinct depictions of the new national allegory Marianne appeared from 1897 onwards. At first, coins of lower denominations with face values of 1, 2, 5 and 10 centimes (Type Daniel Dupuis) were issued featuring the head of Marianne as a representative of the French Republic. She is wearing the Phrygian cap of liberty with an olive branch attached to it – this means: Marianne represents prosperity and peace based on freedom. In addition to the face value and the year, the reverse either featured olive branches or a seated, helmeted Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and knowledge who bestows victory and directs the fate of the state with a laurel branch in her left hand and a flag in her right, protecting a child (the young Republic) which holds ears of grain in its right hand and a hammer in its left – an image that is somewhat reminiscent of the symbol of a later “workers’ and peasants’ state”.

The 1903 25-centime pieces (Type Patey) feature Marianne with a Phrygian cap adorned with laurel branches, indicating victory and glory. The reverse design is rather simple, featuring the face value, the motto of the Revolution and the year. The 25-centime pieces of 1904/05 show the same obverse motif. The reverse, however, features a bundle of rods with axe symbolising the administrative power of the Republic as well as oak leaves representing the strength of the people. Thus, the new motif emphasises the concept of the Republic even more than the old one. However, later coins do not bear the motto of the Revolution. The statement of both issues can be interpreted as follows: in France, the people are in power and they are represented by the state.

France, Third Republic: 20 francs 1906, portrait of Marianne (Type Jules-Clément Chaplain). From Künker auction 349 (2021), lot 4066.

From 1898/99 until the beginning of the First World War in 1914, gold coins worth 10 and 20 francs featuring the portrait of Marianne were minted, too (Type Jules-Clément Chaplain). Her head, covered with a Phrygian cap, is crowned with oak branches as a symbol of strength and resistance. The reverse presents the Gallic rooster referring to the vigilance and the fighting spirit of the Republic.

Later issues of the 3rd Republic show several versions of Marianne: sometimes she is portrayed as ‘liberty’ again, and only the reverse refers to her more complex attributes – sometimes she is depicted wearing just a laurel wreath. Interestingly enough, in the years from 1933 to 1952 (Vichy regime from June 1940 to August 1944), the national allegory presented herself adorned with laurel referring to special achievements, whereas the design did not include attributes that refer to the revolutionary fight for liberty. At the same time, Marianne’s depiction appears to be somewhat mundane (Type Lavrillier), as it is reminiscent of the then ideal of beauty of women, who, by the way, were only granted the right to vote on 21 April 1944 by the Comité français de la Libération nationale (CFLN).

Depictions of Marianne on the coinage of the 4th and 5th Republics will soon be dealt with in a second part of this article.